Art at The Machrie

Will you take tea with Tracey Emin and Pat Douthwaite? Relax fireside beside a John Bellany? Sip whisky beneath the Black Angel, now safe on Islay after its tumultuous journey…?

The Courtyard lounge greets guests to the hotel's impressive contemporary art collection

From collages to oil on canvas, screenprints and a corten steel stag, the eclectic Machrie art collection – personally curated by the hotel’s founder, Sue Nye – is teeming with unexpected treasures.

With works by leading names in Scottish and contemporary art, this calibre of collection would usually be cloistered away in a gallery – hung behind a barrier, with an entrance fee attached. Instead, anyone staying at or visiting The Machrie has free rein to wander and enjoy the rare thrill of discovering inspiring art displayed in a relaxed and intimate setting.

We asked Sue to give us a guided tour of the collection, revealing its standout pieces, stories and secrets...

Made in Scotland: John Bellany to The New Glasgow Boys

With miles of blank hotel walls and bare corridors to fill, some people might call for the help of an art consultant. Not Sue: “I didn’t want to delegate such a personal project to an outside consultant,” she says. “I thought, what if we could start a collection that celebrates contemporary art with a heavy emphasis on Scottish artists? Of course, a collection is subject to personal taste, and it wasn’t really a thought-out process, but slowly, pieces by artists I liked found their place.”

Ailsa Craig by John Bellany

One of the first was Ailsa Craig, by the influential Scottish painter John Bellany, which now hangs in The Courtyard lounge. With its graphic use of colour, figurative subject matter and expressive style, this painting was to set the tone for the pieces that followed as The Machrie’s collection grew.

"I thought, what if we could start a collection that celebrates contemporary art with a heavy emphasis on Scottish artists?"

Covan Hard Man by Peter Howson

Next to join Bellany on the hotel’s walls was Peter Howson, a leading member of The New Glasgow Boys – a group of fiery young artists who helped revive figurative painting in 1980s Scotland. The muscular power of Howson’s pastel on paper, Govan Hard Man, is impossible to ignore as he lunges out of his frame in The Courtyard lounge, angling for a fight. Elsewhere, Poet, a vibrantly coloured 1986 screenprint by fellow New Glasgow Boy Adrian Wiszniewski, sits in prime position in the stag lounge.

Poet by Adrian Wiszniewski

Chicago Joe by Ally Thompson

A contemporary of Howson and Wiszniewski, Ally Thompson is known as the ‘Glasgow Surrealist’. “Sadly, Ally died in 2016,” says Sue, “but I was lucky enough to get a number of his pieces at a studio sale, including Son of Big Apple and Chicago Joe, which you’ll find in the first floor corridor, and Manhattan Mike and The Road Mender in the stag lounge.”

Manhattan Mike and The Road Mender by Ally Thompson

The latest major addition to the collection, L’ange Noir (The Black Angel), by the multi-talented Scottish artist, playwright, screenwriter and designer John Byrne, keeps silent watch over the stag lounge. Half-male and half-female, this androgynous heavenly figure, brought to life in hues of rust and cobalt, is believed to reflect the issues Byrne was experiencing in his relationship with actress Tilda Swinton at the time.

L’ange Noir by John Byrne

Looking at The Black Angel’s steady gaze, you’d never guess its tumultuous journey to the shores of Islay. “The new John Byrne piece is massive – about two metres wide,” says Sue. “It had been professionally packed by the auction house carriers, but unfortunately, by the time it got to Islay, the glass frame was shattered.” An anxious period followed, checking to see if the piece was damaged. Thankfully, the work remained unscathed, but, recalls Sue, “being on an island, it was impossible to get a new piece of glass that size delivered. So I had to ring the auction house and check if it would be alright to replace it with Perspex! They gave the go-ahead – and apparently, lots of pictures now are framed with Perspex because of weight issues – but it was a reminder of the unique challenges of our island setting.”

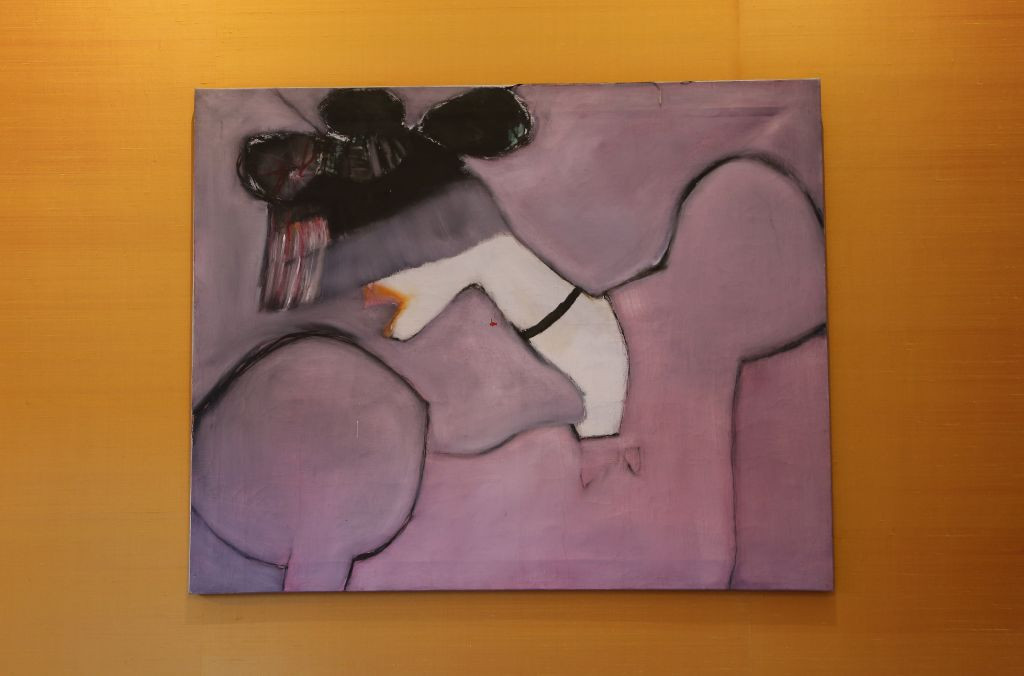

Gwen John Courting by Pat Douthwaite

Earmarking sales of Scottish contemporary art led Sue to one of her favourite artists, the pioneering Pat Douthwaite. An eccentric gang of Douthwaite women – from the Screaming Woman to the Woman with Flower and the Woman with Shawl – depicted with raw emotion and expressive lines, gaze down from The Machrie’s corridors and staircases. But Douthwaite’s sensual oil portrait, Gwen John Courting (Gwen John was a Welsh painter and lover of Auguste Rodin) commands the most attention, on display in the Kildalton room.

Screaming Woman by Pat Douthwaite

Other significant female Scottish artists represented include the world-renowned painter and printmaker Barbara Rae, whose dreamlike mixed media collage, Night Strides, glows in shades of indigo in the ground floor corridor.

And from the snug to the sitting room, the restaurant to the reception desk, a dazzling, personality-packed spectrum of screenprints, oil paintings, textiles and lithographs by acclaimed Scottish artists including Bruce McLean, Dame Elizabeth Blackadder, John Lowry Morrison, Alison Watt, Robert Stewart, Sandra Blow and Eduardo Paolozzi bring inimitable Scottish character, wit and grit to the hotel’s hidden corners and open spaces.

Big names, no barriers: Tracey Emin to Michael Craig-Martin

Dougal the Cow and posters in 18 Restaurant & Bar

But the reach and scope of The Machrie’s collection extends far beyond the Scottish border. A stay here grants up-close-and-personal access to works by some of the leading names in contemporary art. At every turn, something arresting holds your gaze.

Me by Tracey Emin

By front desk, you can become better acquainted with Tracey Emin via her 2019 lithograph self-portrait, Me. Or, as you dine on Hebridean flavours in the restaurant, why not digest the bold colour and graphic compositions of prints by John Hoyland, one of the greatest abstract painters of the post-war period, tour-de-force of British Pop Art, Peter Blake, and pioneering Royal Academician, Terry Frost? Or let Michael Craig-Martin – hailed by the Royal Academy as a “key figure in British art” ahead of their huge retrospective of his work – spur you on in the hotel gym with his vivid stopwatch print for the 2012 Paralympic Games. Craig-Martin’s Violin Plates in Three Sections are also on display by the pro shop.

“There’s a Grayson Perry facemask and plate alongside a Picasso print on cotton in The Courtyard lounge,” says Sue. “I like the idea of all these unusual places where art can be found and enjoyed at leisure.”

A stay grants up-close-and-personal access to works by some of the leading names in contemporary art – at every turn, something arresting holds your gaze.

This subtle democratisation of art is a thread that runs throughout The Machrie collection – and Sue’s motivation in putting it together. From Antony Gormley’s Hands to Yinka Shonibare’s Swinging Headless print, Cornelia Parker’s Wake Up and Patrick Caulfield’s Brown Pot, The Machrie untethers genre-defining contemporary art from the potential exclusivity or stuffiness of a traditional gallery.

The Swinging Headless by Yoni Shonibare

However, this relaxed approach to hanging trailblazing art comes with its own unexpected challenges, as Sue discovered when hosting a wedding. “We have a brilliant oil on pallet work by Bob and Roberta Smith in the restaurant. His work uses text as an art form, and this piece is emblazoned with a big colourful slogan saying ‘What Was I Thinking?’.

"We once had a wedding where the bride realised she would be sitting right underneath the Bob and Roberta Smith slogan painting that says, ‘What Was I Thinking?'"

What Was I Thinking? by Bob and Roberta Smith

“We once had a wedding where they hired the whole restaurant, and the bride realised that in their table layout, she would be sitting right underneath this picture saying ‘What Was I Thinking?’. I mean, can you imagine the wedding photos?! Because the work is an actual wooden pallet that’s screwed to the wall, it can’t be moved – but of course we wanted to make sure everything was just right for the bride, so we carefully covered it for the big day in the end. But for a moment I was wondering what the wedding photographer would say when he noticed!”

Art for the people: Stanley Spencer to Sonia Delaunay

A vintage Bob Dylan poster in one of the hotel bedrooms

Sue’s interest in making art more accessible also explains The Machrie’s impressive collection of artist-made posters.

“By allowing artists to draw directly on the plate, lithography liberated artists from having their work translated by engravers and gave them more freedom of expression,” she says. “And the ability to produce multiple copies democratised the work of artists.”

With posters displayed on the streets, in railway stations and on billboards, “it meant that art was suddenly taken out of galleries and into public spaces, which I’ve always found interesting,” says Sue.

Shipbuilding on the Clyde: Burners 1940 by Stanley Spencer

Original posters by influential artists like Brendan Neilan mingle with the first poster Sue acquired for The Machrie, the rare Second World War print, Shipbuilding on the Clyde: Burners 1940, by Stanley Spencer. Described by Paul Rennie, a leading authority on British graphic design, as “one of the great achievements of British art in the 20th Century,” this powerful image of herculean Clydebank shipbuilders was produced “in large enough scale for the images to be successfully displayed [...] in factory canteens and other venues where the general public could see them.”

Silver Horse by Huw Williams

Framed scarves lead the way to 18 Restaurant & Bar

The Machrie collection also spotlights the many artists who used textiles to get their message out, with works by Picasso, Miro and Dali on display. “One of my favourite artists is Sonia Delaunay,” says Sue. “And, in the 50s and 60s she worked with Liberty London to produce a number of scarves, which we have a few beautiful examples of in the Ben Hogan suite, outside the snug and in a treatment room.”

In the spa waiting area, guests can get lost in the serene scene depicted on the Libres commes L’air scarf by Hermès, which Sue bought “because it reminded me of the geese that winter on Islay every year.”

Other framed vintage scarves found during “nightly eBay trawls,” reveal a recurring golf theme (celebrating The Machrie’s world-class links course), and were among the first items Sue found to decorate the hotel. Guests can spot illustrated golf balls, clubs and trophies in the intricate scarf designs by Hermès, Burberry, Gucci and Ralph Lauren dotted around the interior.

One of the many vintage designer scarves with a nod to golf

Street art in the wild: Banksy to Blek le Rat

Golf-themed scarves and street art might seem to sit at opposite ends of the artistic spectrum, and yet a stay at The Machrie offers the opportunity to admire both in an eclectic melting pot of creativity.

“In a way, I think the diversity of the collection means it has more interest and spirit than if it had been put together by an art curation company,” says Sue. “It’s a personal story, and it grew organically.”

Sheep by Blek Le Rat

“A series of street art pieces by Banksy, Blek Le Rat and Stik fizz with anti-establishment energy”

This mood of unconventionality chimes with a series of street art pieces that fizz with anti-establishment energy from their position close to front desk. There’s Sheep, an iconic 2006 screenprint by the French ‘father of stencil graffiti art’ (and inspiration to Banksy) Blek Le Rat, posters from Banksy’s 2023 Cut & Run show in Glasgow, and a 2018 print by British street artist Stik, known for his socially-conscious murals featuring his distinctive stick figures.

Hare of the dog: Heidi Wickham to Allan Forsyth

Corten steel stag's head by Fabian von Spreckelsen

Travelling from the streets back to the wilderness that surrounds the hotel, a characterful cast of animals – deer, dogs, horses, hares, sheep and cows – call the Machrie’s walls and hallways home. But you won’t find shooting party trophies here. Instead, quirky photographs, lively oil paintings and a mad cow made of (what else?) old rugs, rule the roost.

Corten steel stag's head by Fabian von Spreckelsen

“It's a modern play on the trope of the Scottish country hotel with taxidermy on the wall – with absolutely no dead animals involved!” says Sue, referencing the two-metre corten steel stag’s head by German artist Fabian von Spreckelsen, which presides over the stag lounge fireplace. “It was one of the very first pieces we bought, and we bought it specifically for that fireplace, knowing that a room that size needs a piece with real presence.”

Continuing the stag theme, two 3D lenticular deer photographs by Allan Forsyth appear to follow you around the room, so lifelike are their hologram eyes. Meanwhile, the elegant Silver Horse by ‘the horse painter’ Huw Williams bows its head to guests descending the staircase.

But of all the paintings at The Machrie, the one that gets “the most attention” is arguably the Big Hare in The Courtyard lounge, by Irish contemporary artist Heidi Wickham, says Sue. “Hares are so prevalent on The Machrie golf course. You just look out the window and they’re everywhere.” Tall Dog, also by Wickham, stands guard in the Courtyard lobby.

Hare by Heidi Wickam

Lastly, but by no means least, are Dolly the Sheep and Dougal the Cow. “Dolly (named after the first mammal ever cloned at the Roslin Institute in Scotland) was a very early acquisition from an auction and has been in the reception area for years, where she wore a hard hat during the final stages of the build,” says Sue. “She’s lost the hard hat now but sometimes sports RNLI wellington boots and likes to get dressed up at Christmas. In spring she has a lamb.” There have been many offers to buy Dolly, says Sue, but all have “been resisted.”

Dolly the Sheep

Dougal started life in the Liberty rug department. “I went in and saw this cow made of rugs, and I begged them to sell it to me. Many people don’t like taxidermy, but Dougal is much better than taxidermy.”

And the collection continues to grow. “It’s ever-evolving,” says Sue. “It's not static – pieces move, new pieces arrive. It’s certainly a good reason for people to come back and see what’s changed, I think. And there are lots of works I’m still hoping to find, so I’m always trawling auction houses! It’s a work in progress.”

Blossoming from a single pink Hermès scarf and a steel stag over a fireplace to a spirited, unique and astonishingly diverse ensemble of acclaimed modern art, The Machrie collection is worthy of space in any gallery – let alone a hotel on the remote Hebridean island of Islay. And yet this unexpected setting – amongst undulating links, miles of golden sand, wild moorland and the contented daily comings and goings of hotel guests – is exactly what makes it so compelling.