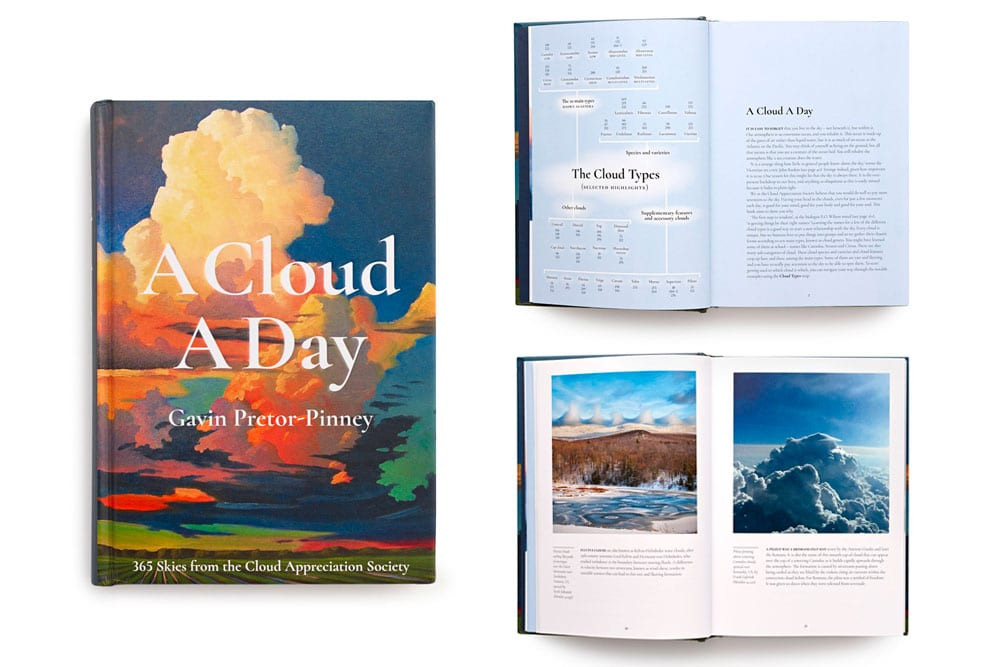

The man with his head in the clouds

(8 minute read)

For too many, clouds are shorthand for gloom and doom. But author and founder of The Cloud Appreciation Society, Gavin Pretor-Pinney, rallies us to see them a source of joy…

A host of lenticularis over Ullswater, the Lake District, UK. © Stuart Bullas

How sweet to be a cloud. Floating in the blue! – A. A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh (1926)

When was the last time you lay back and looked up at the clouds?

As children, we’re all committed cloudspotters – spying dragons, castles, faces and whatever else our fertile imaginations can conjure. But as adults, unless they happen to drench us in a sudden downpour, or play havoc with our carefully laid picnic plans, we rarely stop to give them a second thought.

And yet clouds are a constant, unavoidable presence in our everyday lives. They shape our moods. They dictate our activities. They influence our daily choices, from the way we travel to the clothes we wear. But for the most part, we’re oblivious to them, staring down into our phones or gazing into screens while they change, shapeshift and metamorphose right above our heads.

Gavin Pretor-Pinney is someone who’s devoted his life to making sure clouds get the attention they deserve.

As author of The Cloudspotter’s Guide and founder of The Cloud Appreciation Society, he spends much of his time thinking about nothing but clouds. Documenting unusual sightings, collecting and collating pictures gathered by the society’s members, developing education packs, writing books, and above all, pondering humanity’s relationship with clouds – their meanings and metaphors, and the lessons they can teach us about the planet we call home.

A layer of Stratus over Loch Tay, Perthshire, Scotland. © Catherine McGregor

A community of cloud-spotters

“It began by accident, really,” Gavin explains. “I’d always been fascinated by clouds, and way back in 2005, a friend at the Port Eliot Festival asked me to come along and do a talk. I called it the Inaugural Lecture of the Cloud Appreciation Society, just because it sounded like an interesting name and a fun thing to go along to. That was how it all started.”

Sixteen years on, the Cloud Appreciation Society has gone from part-time enthusiasm to full-time vocation. With a global membership of more than 50,000 people, and communities of cloudspotters stretching from San Francisco to Seoul – not to mention three bestselling books (The Cloudspotter’s Guide, The Cloud Collector’s Handbook and A Cloud A Day), a TED Talk that’s been watched online by 1.3m people, and even his own cloud spotting app – Pretor-Pinney has become one of the world’s most eloquent advocates for the enduring importance of clouds.

A storm system spotted from the Cobb, Lyme Regis, Dorset, UK. © Catherine Alexander

“The amazing thing about clouds are that they’re this part of nature which comes to us, no matter where we are.”

“The amazing thing about clouds are that they’re this part of nature which comes to us, no matter where we are,” he says. “We could be stuck in an apartment in the middle of a city, with just a window or a balcony, and yet the sky is a part of nature that is still within our grasp. And it’s a democratic one: everyone has equal access to this thing we call our atmosphere.”

But why clouds? Why not an Appreciation Society for sunrises, or star-spotting, or just the sky in general?

“For me there’s always been something magical and contradictory about clouds,” he says. “Their ability to disappear and reappear at will; the way they’re in this constant state of change and metamorphosis. They’re invitations to our imaginations. They pass over us like emotions do. A cloud appears out of the blue like an idea appears in an absent mind.

“But they’re also the result of physics; the changing phases of water caused by changes in temperature and air pressure. I find that a wonderful marriage, really. As G.K. Chesterton said ‘There are no rules of architecture for a castle in the clouds.’ That idea that they’re free and ever-changing affects us emotionally. I love that interplay.”

Lenticularis over the Lake District near Windermere, UK. © Ali Reynolds

The contrariness of clouds

There’s also something of the enthusiastic eccentric about Pretor-Pinney’s contrarian passion for his subject. The British, he admits, have a more complicated and ambivalent relationship with clouds than most nations – but he thinks it’s our very familiarity with them that makes them so fascinating to us.

“There are plenty of people for whom the clouds have ruined weddings, or barbecues, or holidays at the seaside,” he says. “In this country we often feel there are too many clouds. But people in California, where we also have a lot of members, are desperate for clouds. They have a completely different relationship with them. That gives a richness and depth to the subject, I think.”

“For me there’s something magical and contradictory about clouds. They’re invitations to our imaginations.”

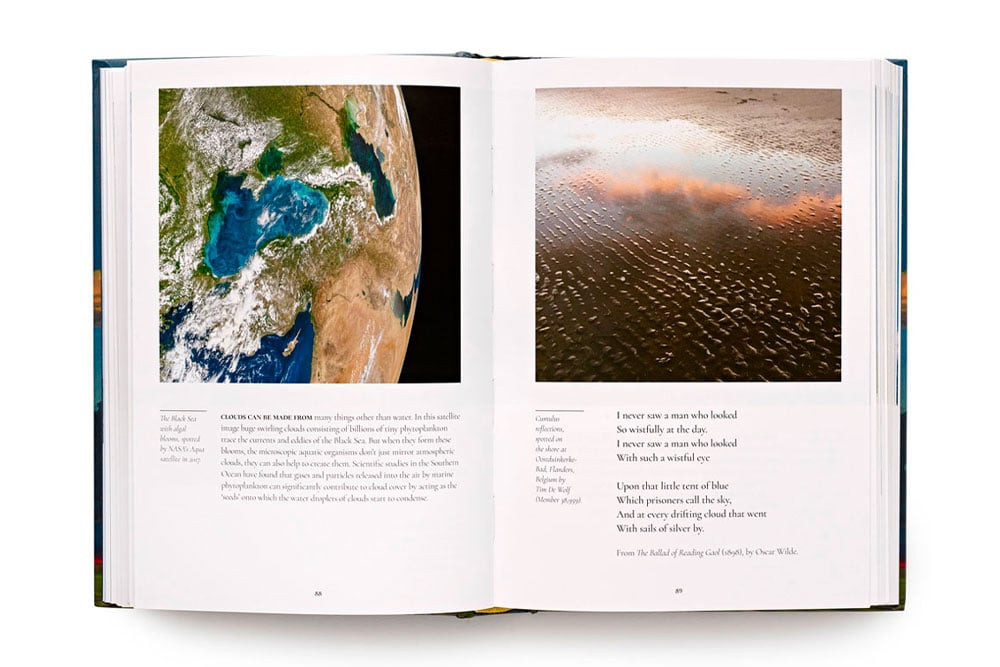

Clouds, he believes, can also serve as a unifying force in a world increasingly dominated by division and polarisation. The search for shared community is one of the reasons he thinks the Cloud Appreciation Society has flourished over the last decade. Ultimately, no matter which end of the political spectrum or which corner of the globe we occupy, we see the same sky; we’re drenched by the same rain showers; and, when we allow ourselves time, we find the same pleasure in watching the clouds scud by. And clouds also contain salutary lessons on the most pressing issue collectively facing us: climate change.

“One of the reasons people dislike the clouds is because they don’t bloody well do what we want them to,” he says with a wry laugh. “Of all the aspects of nature, they’re the most ungovernable and uncontrollable. That’s frustrating – but the belief that we’re in charge of nature has, in many ways, been part of the problem. Becoming more conscious – and appreciative – of those parts of nature, like clouds, that are out of our control can be very helpful, I think.”

Sometimes, however, it’s equally important to just watch the clouds with no agenda other than simply enjoying them for their own sake.

“We all say we have no time for something as frivolous as looking at the clouds,” he says. “But that’s precisely the reason why it’s a valuable thing to do every now and then. Clouds are universal; they bring us together. If you ask me, I think we need them now more than ever.”

Cloudspotting 101

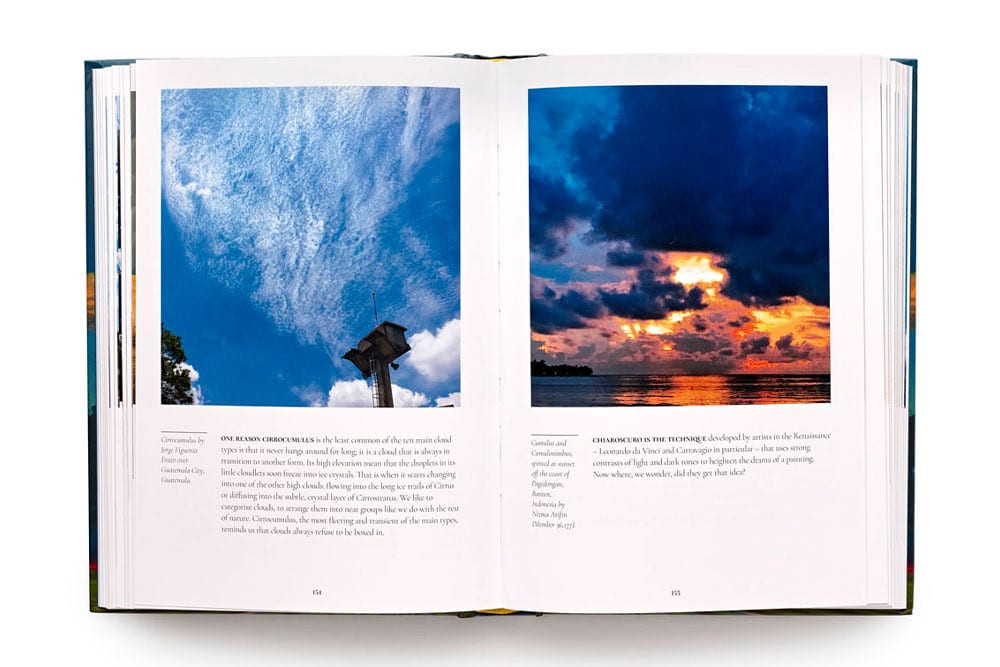

Cumulus The classic white, cotton-wool clouds that appear on a sunny day. They are the best ones for spotting shapes in. When they form higher up as clumpy rolls or patches, they become altocumulus. Higher still, they become cirrocumulus.

Stratocumulus A close cousin of the cumulus cloud. If you’re sitting under a largely cloudy sky filled with many clumps and puffs, connected or with a few patches of sky in between, that’s likely to be stratocumulus. It’s similar to altocumulus, but the cloudlets are usually closer together and more densely packed.

Cirrus The painter’s cloud: wispy and brushstroke-like, named after the Latin for a lock of hair. They are the highest form of cloud, composed of ice crystals in the troposphere that are dispersed and elongated by high winds.

Cumulonimbus The classic storm cloud. Dark and brooding, these ominous sky-filling clouds often spread out at the top like an anvil. They herald bad weather.

Stratus The low, grey blanket of cloud that lurks around on heavily overcast days, at altitudes of no more than 1500 feet; it looks similar to fog. When it covers the sky at higher altitudes, it is known as altostratus.

Nimbostratus The main rain-bringing cloud. If you’re stuck inside looking at a flat, featureless grey sky and drops of rain on the window, chances are it’s nimbostratus that’s the culprit.

Lenticularis An unusual cloud formation shaped like a flying saucer. It’s believed to have been the cause of many UFO sightings.

For more handy cloud-spotting tips, download the free ‘Cloud-A-Day’ app from the Cloud Appreciation Society’s website.